Beneath the Snows of Winter

By: Michael Gambino / Curator / Edith G. Read Wildlife Sanctuary

Winter is a challenging season for wildlife. The adaptations and survival strategies of many species here in the cold Northeast are tested once more, as they have been for thousands of years.

Some animals have already headed south to warmer climes by the time winter snows cover the landscape. Others have retreated to their cozy hibernation chambers deep below winter’s killing cold and will sleep until the warmth of early spring returns.

There are, however, animals that do not migrate or enter dens to escape the harsh winter months. Animals with a larger body mass such as the White-tailed deer generate a large amount of heat that is trapped by the thicker layer of hair and fat gained during the autumn season. Other medium-sized animals like the Eastern Coyote, Red Fox and the Eastern Cottontail rabbit are protected in a similar fashion, though they develop a dense fur coat that keeps them warm and dry. These larger animals can be seen during winter, and their tracks are readily observable in the snow.

So what about all the small animals like chipmunks, mice, shrews, and voles? How do they survive the killing cold? Chipmunks are among the animals that spend winter underground, not truly hibernating, but rather sleeping deeply. They awaken periodically to use the latrine area of their burrow, or munch on an acorn stashed in their stockpile of winter food before returning to their bed chamber for more sleep.

The abundance of Short-tailed Shrews, Meadow Voles, and various mouse species are active all winter long in fields and forests. They are secretive creatures who forage beneath the cover of leaf litter and dry grasses for nuts and seeds and torpid insects. Hawks, owls, coyotes, and foxes are looking for food too, and a careless vole who finds himself in thin cover may end up as a meal for these predators.

When a snowstorm covers these habitats with a foot or more of snow, it’s actually good news for these small mammals. This is because not only are they now more protected from predatory animals, the snow acts as an insulator that protects these small animals from bitter cold winds and below freezing temperatures.

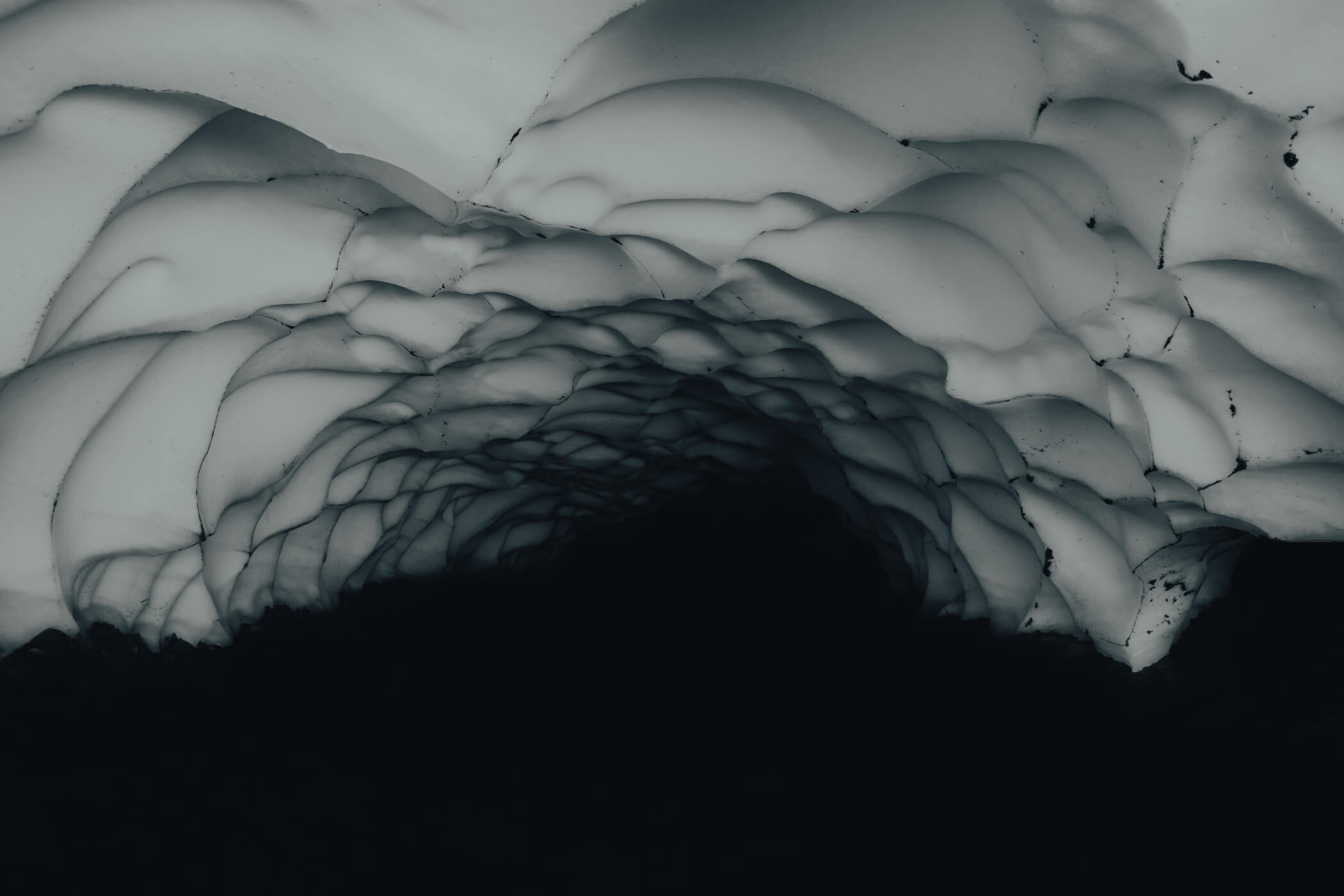

This place beneath the snows of winter is called the subnivean zone, and in this zone, small mammals can move about freely searching for food, still under the matted dry grasses and protected by a roof of ice and snow. This roof is created as the heat from the earth melts the snow and water vapor is created in the resulting space between snow and earth. This vapor rises to the roof of snow pack and condenses, forming a thin layer of protective ice that stops sub-zero winds from getting in from above and slows heat loss from below. The subnivean zone temperatures are just a degree or two above or below freezing for the whole winter – even into early spring when the outside air temperature above the snowpack warms considerably.

If you are thinking this sounds like the Inuit igloos, then you are correct. The tiny spaces between snow flakes and ice crystals actually trap heat from the earth. Any material or substance with tiny pockets of dead air space will trap heat. This is a fundamental principle of most insulation. It’s why fur and hair are terrific insulators for larger animals, and why your wool jacket keeps you toasty warm.

The subnivean zone has other elements that make it an amazing winter habitat. There is no concern for lack of oxygen since there are many air shafts created by stems of plants and grasses and tree trunks in the snow that allow gasses to be exchanged in the subnivean world. There is even enough light that filters through several feet of snow to reach the ground. This helps explain why the plants close to the ground can keep growing while buried under winter snow. As winter approaches spring, the thawing and refreezing of snow creates a clearer layer of ice crystals that allows even more light to filter down, letting the inhabitants know that their winter world will soon be disappearing.

Plant life sustained by the subnivean twilight helps feed the creatures that dwell there. There are also still unclaimed nuts and seeds, and insects to snack on, and always there is the opportunity to chew on the inner bark of trees. In spring when the last of the snowpack is melted, you can see evidence of the activity under the snow. Trees and shrubs will often be stripped of bark matching the height of the former snowpack. With snow roofs melted away, you can see etched into the grass and soil of golf courses and wild meadows the maze of tunnels and trails used by mice, voles, and shrews as they chewed and stomped their way to and from feeding locations for months.

While all this sounds great for the little beasts that live under snow, what about the hungry predators? How do they find food when all is covered in white? Owls have amazing hearing, and can actually hear the squeaks and squeals of the snow-hidden animals and will actually plunge into deep snow to capture a no doubt very surprised rodent from the subnivean world. The same goes for coyote and fox. With their large ears and keen sense of hearing, they stop and listen intently for the sound of scratching, chewing and soft padding of tiny feet under the snow. When a fox zeroes in on her prey, she leaps straight up and literally dives into the snow, crushing the escape tunnels of the rodents. Then she simply collects her meal.

This winter when you are outside enjoying the cold natural beauty of the season and all seems quiet and asleep in the woods and meadows, think about all that is taking place cloaked in secrecy beneath the snow.

Nature note: What’s the Difference between hair and fur? “Hair” and “fur” are names usually applied to different animals type of hair growth. In their winter coats, White-tailed deer have coarse, thick strands of hair that are hollow and help trap body heat along with a denser, kinkier mat of hair close to the skin that does most of the insulating. A fox or a rabbit has hair that is very fine and grows very dense. A chinchilla has perhaps the finest (softest) hair of all terrestrial mammals with 50-80 hairs growing out of a single follicle compared to a human which only grows 2-3 hairs per follicle. Humans, it seems, are still tropical creatures!